Answer: The nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson's disease include psychiatric symptoms, cognitive difficulties, changes in sleep patterns, and gastrointestinal symptoms.

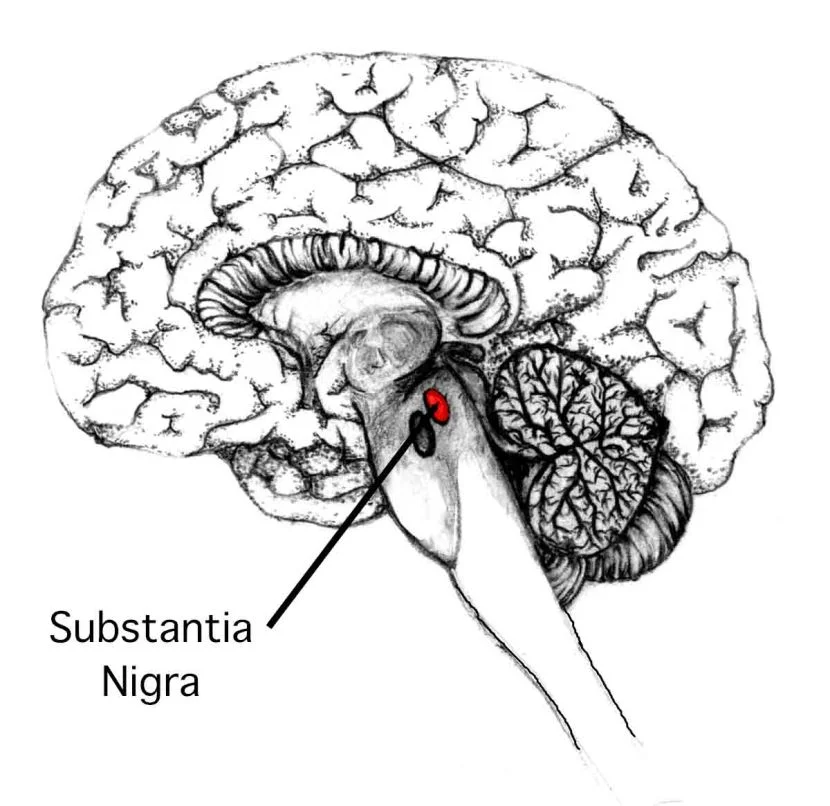

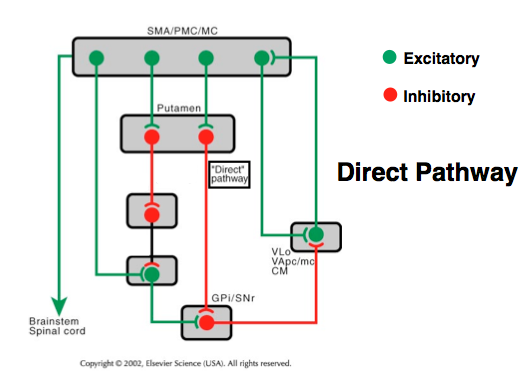

Parkinson's disease is best known for producing difficulty in the initiation of movement, a resting tremor, bradykinesia (slowness in movement), and a slow shuffling gait. These symptoms are all considered motor symptoms, since their outward appearance becomes manifest in the way the brain is controlling the body parts. Most of these motor symptoms are believed to result from the loss of dopaminergic cells in the substantia nigra, leading to a decrease in dopamine tone in the striatum. The motor symptoms are responsive to treatment with L-DOPA, which effectively replaces the dopamine loss observed in Parkinson’s disease.

However, in addition to these motor symptoms, Parkinson's disease also can produce nonmotor symptoms in patients. Some of these nonmotor symptoms may occur before the onset of the motor symptoms.

Psychiatric symptoms of Parkinson’s disease

One common psychiatric symptom that appears in Parkinson’s disease is depression. It is estimated to occur in just under half of all patients with Parkinson's ( Weber WE, et al. A systematic review of prevalence studies of depression in Parkinson's disease), making it the most common neuropsychiatric nonmotor symptom. Appearance of depressive-like symptoms and minor depression are often predictors of the necessity of early dopamine treatment or major depression later in the progress of the disease (Depression and Parkinson’s Disease: Current Knowledge).

Anxiety is another common non-motor symptom. Estimates range from around 30 to 50% (Anxiety and self-perceived health status in Parkinson’s disease.) Anxiety disorders are an underreported symptom of Parkinson’s disease, although it may lead to a significantly lower quality of life for the patient. The patients can also experience a social anxiety regarding their perception of their own status as a patient (Social anxiety in patients with Parkinson’s disease.)

Mood fluctuations are also a common nonmotor symptom of Parkinson’s disease. These changes in mood may occur rapidly, up to several times a day. Unsurprisingly, they often correlate with whether or not the patient is currently experiencing Parkinsonian symptoms. When the patient is unable to move as normal, the “off state,” they experience a lower mood. However, during the “on state” when they can move as normal, they experience elevated mood (Mood changes associated with "end-of-dose deterioration" in Parkinson's disease: a controlled study.)

Cognitive symptoms

The most common cognitive difficulty that occurs in Parkinson’s disease is a slowness in processing, of bradyphrenia. Mild cognitive impairment has a prevalence of around 80% within 15 to 20 years of initial diagnosis (Cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease: the complex picture).

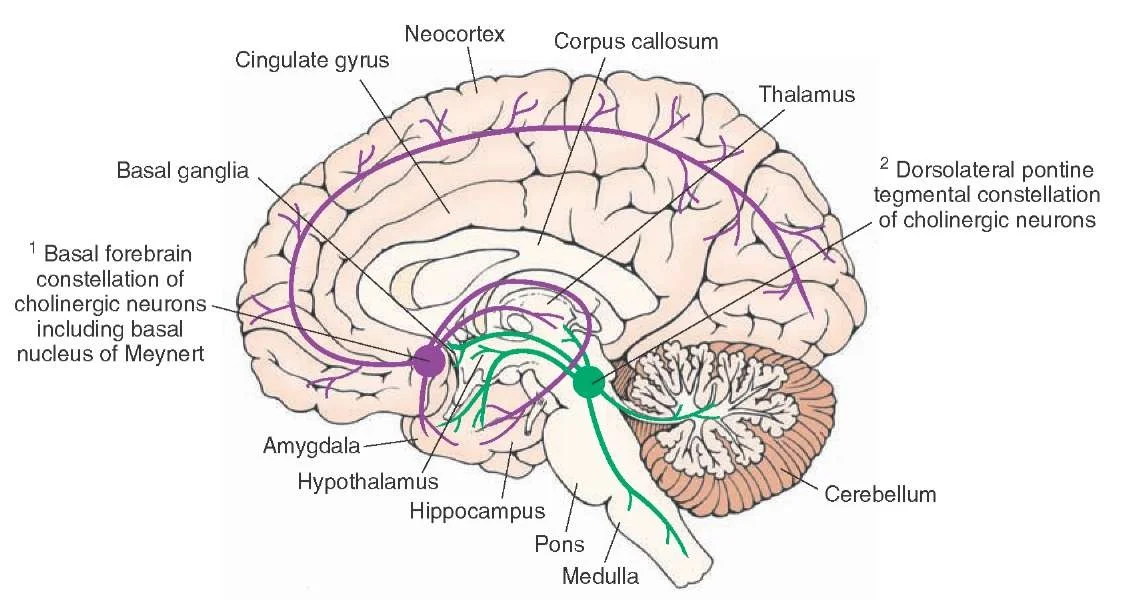

Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) may be observed in late stages of the disease. There is an FDA approved drug called exelon (Rivastigmine) that may help decrease the symptoms of this dementia. Rivastigmine acts to increase the concentration of acetylcholine by inhibiting it's enzymatic breakdown by acetylcholinesterase.

The cognitive symptoms are very difficult to diagnose in Parkinson's disease. Often times, the diagnosis is clouded by normal age-related cognitive decline or the influence of some other disorder.

Disturbances in sleep patterns

Insomnia, a disruption of normal night time sleep, is predicted to affect about 80% of patients with Parkinson's disease (Sleep disorders and sleep effect in Parkinson’s disease.) Insomnia can manifest itself in several ways, including a difficulty in falling asleep, difficulty in staying asleep throughout the night, or waking up too early. All of these symptoms results in decreased sleep at night, leading to increased daytime somnolence (tiredness.) Insomnia dramatically decreases the quality of life of a patient. A drug such as trazodone, with its dual effects of increasing sleepiness and improving mood by acting as an antidepressant, can help relieve both the insomnia and the depression (Ten-year trends in the pharmacological treatment of insomnia.)

In addition to insomnia, people with Parkinson's disease also experience less restful sleep compared to the age-matched counterparts. For example, they spend less time in deep sleep and REM sleep. Deep sleep and REM sleep are very restorative times, and can help the body recover from the stresses of daytime (https://www.apdaparkinson.org/what-is-parkinsons/symptoms/sleep-problems/).

REM behavior disorder (RBD) is another symptom that may be comorbid with Parkinson's disease. In REM behavior disorder, there is a failure of sleep paralysis that allows the sleeping patient to physically act out their dreams, sometimes violently. These symptoms may become more severe with treatment with L-DOPA. Interestingly, the appearance of REM behavior disorder may act as a diagnostic tool for Parkinson’s disease, as almost 80% of RBD develop some sort of neurodegenerative disorder (Parkinson risk in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder).

Gastrointestinal symptoms

A wide variety of gastrointestinal symptoms may also be comorbid with Parkinson's disease. Some of these include a difficulty in swallowing foods or liquids (dysphagia), constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, or frequent nausea. These symptoms are generally underreported clinically, even though the patients or their caregivers note these difficulties they are experiencing.

It has been theorized that these gastrointestinal symptoms of Parkinson’s disease precede the motor symptoms. According the the Braak hypothesis of Parkinsonian pathology, nerve cell dysfunction in the form of synucleinopathy starts in the autonomic nervous system before moving into the central nervous system, where it can then damage the cells of the substantia nigra.